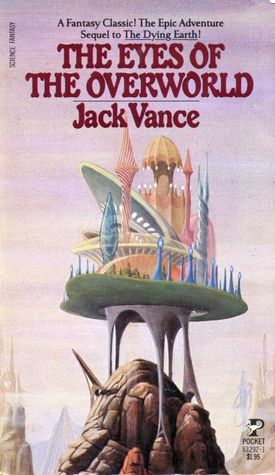

The Eyes of the Overworld (aka. Cugel the Clever, Jack Vance, 1966) is the second novel in the The Dying Earth series. It follows the (mis)adventures of the rogue Cugel, on his journey across the world back to his home in Almery after banishment by the Laughing Mage, Iucounu, brought upon by Cugel’s attempted burglary of Iucounu’s manse. Charged with retrieving the Eyes of the Overworld, Cugel is flown to distant, unfamiliar lands with only his wits and a magical sustenance-providing amulet to aid him.

As in ‘The Dying Earth’, grimness is again the order of the day. Broken into the same stand-alone story structure as its predecessor, the novel covers Cugel’s trials in his quest to return home. One chapter sees Cugel attempting to cross a vast desert, while another sees him navigate a mountain range haunted by a dark past. Each chapter has Cugel triumph via use of his intelligence and total disregard for human life. Treasures are stolen, towns ruined, people killed. It is not a happy story for the people of Earth, unless your name happens to be Cugel.

One thing I’ve noticed about the story-per-chapter approach: Either the novel was originally serialised a chapter at a time in a magazine, or Vance thinks his readers have a very short attention span: Some facts on Cugel’s quest are constantly repeated, such as his unfortunate liver-mate Firx’s presence, implanted by Iucounu to keep Cugel on task. Granted, this is an important plot point, but given how Firx is often referred to anyway, it seems excessive. I’ll have to believe that the novel was originally serialised, otherwise this sort of repetition could only reflect badly on Vance.

Cugel himself seems to be a more developed version of Vance’s earlier rogue from The Dying Earth, Liane the Wayfarer. Cugel and Liane share a number of traits, including psychopathy and a taste for clever trickery. While Liane is the more explicit murderer, Cugel avoids having to end lives without there being something in it for him. Or if he’s annoyed. Despite this streak of kindness, Cugel obviously does not make a sympathetic protagonist, as he leaves only confusion and death in his wake, sometimes unintentionally but usually for personal gain.

Vance’s writing style has virtually unchanged since The Dying Earth, except the nature of Cugel’s character and troubles mean that there is a great deal more humour and pathos than in the previous novel. Cugel blunders his way from town to town, attributing to cleverness what might be more accurately termed luck. The ironic consequences of his actions — once bringing a curse upon himself that he was purposefully trying to avoid — bring smiles, and the reader will find equal measures of schadenfreude and catharsis in Cugel’s plight.

As a character, Cugel is fairly static, perhaps comically so. Being the now stereotypical lone wolf rogue psychopath, there isn’t much room for character growth, although Vance does provide the occasional surprise and insight into Cugel’s less vile side. Similarly to The Dying Earth, no other characters persist across chapters, or if they do they do not stick around for very long. They have no time for development because of this, but given that Cugel’s personality doesn’t go anywhere either, maybe this is something for Vance to work on.

Vance keeps up the magic from the last novel, showing off a vast imagination in self-contained doses. For instance, the secret of the Mountains of Magnatz, while no doubt bearing great importance in the world, is never brought up after the end of the chapter. But regardless, the stories inside each chapter are fresh and interesting, featuring trials such as a trip one million years into the past, a battle of wits against a race of enterprising rat-men, and a visit to a town of people who see another, far superior version of the world to that inhabited by the other citizens of Earth.

It seems unfair to pick on The Eyes of the Overworld for employing old fantasy tropes and old-school biases, so I won’t. But reader be aware that this novel is from an earlier age, about an age where social attitudes have deteriorated even further.

There’s a lot to like about The Eyes of the Overworld, even if there is very little to like about the protagonist himself. After a couple of chapters, the routine becomes clear and the reader is left wondering how Cugel will extract himself from the next problem, and how much damage he’ll cause in the process. Playing with reader expectations becomes a key point of enjoyment in the novel. I had a lot of fun trying to guess Cugel’s twisted solutions to his dilemmas, and more joy was forthcoming each time Vance revealed Cugel’s next feat of skulduggery.

If you enjoyed the ‘Liane the Wayfarer’ and ‘Ulan Dhor Ends a Dream’ chapters of The Dying Earth, The Eyes of the Overworld is more of the same: Roguery and daring adventures in a harsh, uncaring world. Being a stand-alone novel, I can recommend The Eyes of the Overworld to any fans of underhanded tactics and less-than-moral protagonists, even if they haven’t read the first novel in the series. It’s about the same length as The Dying Earth, so if you have a couple of evenings to spare, it’s well worth a read through.