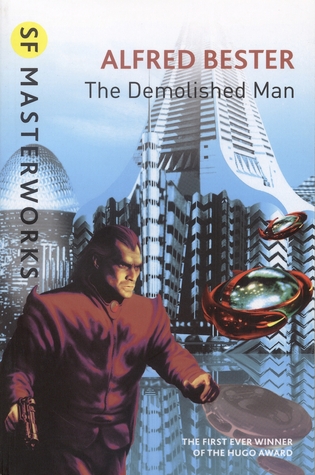

The Demolished Man (Alfred Bester, 1951) is a science-fiction inverted detective story, equal parts Ocean’s Eleven and Death Note. The novel tells the story of business monolith Ben Reich’s mission to murder rival conglomerate owner Craye D’Courtney in a world where psychics (or espers, ‘extra-sensory perception’-ers) form a significant proportion of the population and a pre-meditated murder hasn’t gone undetected or unsolved for over seventy years. Ben’s primary foil is the police prefect Lincoln Powell, top-class esper who is able to ‘peep’ through even the strongest mental blocks that a suspect can put up.

Reich, non-esper CEO of planet-spanning empire Monarch, is motivated by horrible nightmares he experiences whenever he sleeps. Shaken from sleep by visions of a man with no face, Reich decides the only way to end his torment is to remove the greatest source of stress from his life: Business rival D’Courtney of the D’Courtney Cartel. Before commiting himself to his plan, Reich makes a failed attempt to reach an understanding with D’Courtney, offering a merger between their two companies. The rejection cements Reich’s resolve: D’Courtney must die.

The premise alone is not super exciting – after all, it places Reich in the ‘jealous businessman’ archetype – but Reich’s barriers to committing the perfect murder make the plot thick and interesting: Anyone with murderous intent sticks out like a sore thumb in a city of psychics, so Reich has to construct a plan that will be untraceable and undetectable on both the psychic and physical levels.

Reich is a complex character: Thoroughly likeable, superbly witty, and naturally, a psychopath. Reich considers himself someone with the killer instinct: Able to follow through on a plan even when things start going to hell, improvising on the fly to make things work. Just how far will he go to rid himself of the faceless man, and avoid the ultimate punishment: Demolition?

His antagonist (and our dual protagonist) Lincoln Powell was born with the highest level of psychic power. While highly sensitive and more than a little mischievous, Lincoln has problems in love. The Guild of Espers usually only accepts married people as president, and Lincoln’s refusal to marry has effectively halted his progress. Columbo springs to mind when thinking of the prefect, although Powell has the added advantage of actually being psychic rather than having the trench-coat detective’s stunning hunches.

So it’s time to dive into the story a bit more, maybe the first quarter of the novel. So here’s your mild spoiler warning.

After plotting and preparing to near-perfection, Reich’s plan goes off mostly without a hitch, barring the complication of the sudden appearance of D’Courtney’s daughter and the disappearance of the murder weapon. Lincoln is assigned to the case, the first of its kind in decades. Lincoln almost immediately deduces and reads Reich’s guilt, but as an esper’s ‘peeping’ is not admissible in court Lincoln needs to put together a complete case against Reich by finding evidence in the three areas satisfying the police crime computer: Motive, opportunity, and method. Here’s a quick gripe: Why is esper evidence not allowed in court? Sure, you need to trust the reporting esper, but why not just make all the judges espers too? I’m sure there’s a way to make this work. But I suppose that wouldn’t make compelling reading, now would it?

The remainder of the story deals with the cat-and-mouse act between the duo: Lincoln expertly identifying all the loose ends to investigate, Reich having already figured out a way to tie them up without implicating himself. The novel is very much the definition of a page-turner: Barely a page goes by without some new event rocking the case, or if the world isn’t busy being shattered the characters are delivering engrossing, clever dialogue to each other.

Speaking of clever dialogue, The Demolished Man has an interesting mechanic when it deals with interactions between psychics: Psychics do not necessarily have to speak in sequence, nor linearly. Of course, why would they limit themselves like that? In the novel, they transmit images to each other at lightning fast speeds. The novel occasionally offers a glimpse into how this might look, providing diagrams of words laid out in odd formations, requiring the reader to spend some time decoding what is being communicated. This paints a picture of just how brilliant the espers are. The author doesn’t overdo this: There’s only a handful of cases where espers communicate in a less traditional way, and Bester will usually write out the dialogue in the more standard A speaks, B speaks form. This is welcome, because the readers aren’t espers. Probably.

I have only a few complaints: First, the twists are obvious. Maybe they’re only obvious because we’ve had so many similar twists in the years since this novel came out, but the book does rely off of the reader not paying too much attention. There’s one particularly nasty offender early on, which you can catch even before a tenth of the way through the book, before it’s revealed properly at the one-quarter mark, and then again near the dénouement if you still haven’t worked it out. This would be fine, if it wasn’t such a central insight into why the plot is happening! That said, guessing or not guessing the twist won’t take away enjoyment from the book. So don’t worry if you think you know where things are going, there’s plenty more to keep you entertained along the way.

Secondly, the ending feels rushed. There’s a huge plot device that is introduced by Lincoln out of nowhere, and it seems like it only exists in order to wrap up the story. It’s a fun plot device, don’t get me wrong. It’s just so deus ex machina, I wonder if the novel could have benefit from an extra chapter or two, or a Chekov’s Gun earlier on.

Finally, the resolution for Lincoln is also pretty weird. It’s not something I’ll discuss in detail, but I’m not sure if you were meant to take away a different idea about Lincoln given his last actions in the book. The emotions he ends up expressing are not what I would associate with someone we’re meant to consider a hero. Maybe the intention was to show just how progressive they are in the future.

In conclusion, the story is solid, the characters have rich personalities, the writing is a pleasure to read. There’s some exciting ideas, some flawed executions, and overall a good book. I’m amazed it was written in 1951! I’d recommend it easily to any fans of the science fiction genre. Even the less sci-fi minded fans of traditional crime fiction could find enjoyment in The Demolished Man.

– Matthew